Archive

Solving Scramble With Friends – a tale of three data structures

Solving Scramble with Friends – A tale of three data structures

This post aims to illustrate how to solve Scramble With Friends/Boggle and the techniques and data structures necessary. In particular, we will see how to prune an enormous search space, how to use recursion to simplify the task, and the relative performance of three different data structures: an unsorted list, a sorted list with binary search, and a trie.

Problem statement

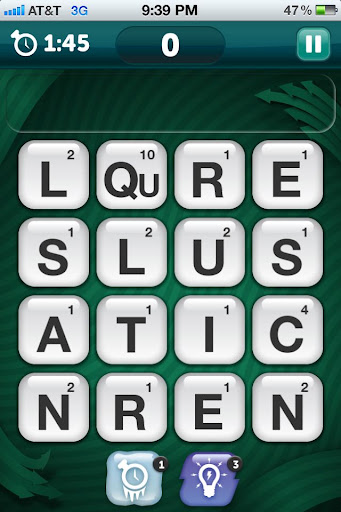

Given an N x N board, (4×4 in case of Boggle and Scramble with Friends), find all of the paths through the board which create a valid word. These paths must use each tile at most once and be contiguous; tile N must be adjacent to tile N – 1 in any of 8 directions (North, Northeast, East, Southeast, South, Southwest, West, Northwest).

In this example, ANT is a valid solution in the bottom left corner, but NURSE is not because the Ns are not located next to the U.

Most naive approach

First, imagine that we have a method that, given a path through the board returns all valid words that starts with that path, called DoSolve. For instance, DoSolve(['Qu']) would return all the valid words (and their locations) that start with Qu. DoSolve(['N', 'E']) would return all the valid paths that start with N followed by an E. With such a method, it is trivial to solve the problem. In pseudocode:

Solve(board):

solutions = empty list

for each location on board:

append DoSolve(location) to solutions

return solutions

The tricky part is, how do we make DoSolve work? Remember that it must

- return only valid words

- return only words that are formed from contiguous tiles

- must not repeat any tiles.

The easiest way to solve this problem is through recursion. As you probably remember, recursion is simply when a method calls itself. In order to avoid an infinite loop (and eventual stack overflow), there must be some sort of stopping criteria. As it was taught to me, you have to be sure that the problem becomes smaller at each step, until it becomes so small as to be trivially solved. Here’s that basic algorithm:

DoSolve(board, tiles_used)

solutions = empty list

current word = empty string

for letter in tiles_used:

append letter to current word

# 1 - ensure that the word is valid

if the current word is a valid word:

append current word to solutions

most recent tile = last tile in tiles_used

# 2 - ensure that the next tile we use is adjacent to the last one

for each tile adjacent to most recent tile:

# 3 - ensure that we do not repeat any tiles

if tile is on the board and tile hasn't been used previously:

new_path = append tile to copy of tiles_used list

solutions_starting_from_tile = DoSolve(board, new_path)

append solutions_starting_from_tile to solutions

return solutions

This will work, but it suffers from an incredible flaw. Do you see it?

The problem is that this method will waste an inordinate amount of time exhaustively searching the board for solutions even when the current path is completely useless. It will continue to search for words starting with QuR, QuRE, etc., etc., even though no words in the English language start with these letters. The algorithm is still correct, but it can be optimized very simply.

Pruning the search space

Those with some algorithms background might recognize the code above as a modified form of a depth first search. As described previously, a depth first search will exhaustively explore every possible path through the board. We can vastly improve the efficiency of this algorithm by quitting the search early when we know it won’t be fruitful. If we know all of the valid words, we can quit when we know that no word starts with the current string. Thus in the previous example, if the current word built up so far were “QuR”, the algorithm could determine that no words start with QuR and thus fail fast and early. This optimization will not affect the correctness of the algorithm because none of the potential paths we eliminate could possibly lead to a valid word; by constraint #1 this means that none of those paths would have ended up in the list of solutions in the first place.

How much does this save? On random 3×3 boards, The fastest implementation I have is sped up by a factor of 75. Solving 4×4 boards without pruning is infeasible.

Basic Python implementation

Assume as a black box we have two methods IsWord(string) and HasPrefix(string). The pseudocode above can be expressed with Python (forgive the slightly modified parameter list; I found it easier to write it this way):

def DoSolve(self, board, previous_locations, location, word_prefix):

"""Returns iterable of FoundWord objects.

Args:

previous_locations: a list of already visited locations

location: the current Location from where to start searching

word_prefix: the current word built up so far, as a string

"""

solutions = []

new_word = word_prefix + board[location.row][location.col]

previous_locations.append(location)

if PREFIX_PRUNE and not self.HasPrefix(new_word):

if DEBUG:

print 'No words found starting with "%s"' %(new_word)

return solutions

# This is a valid, complete words.

if self.IsWord(new_word):

new_solution = FoundWord(new_word, previous_locations)

if DEBUG:

print 'Found new solution: %s' %(str(new_solution))

solutions.append(new_solution)

# Recursively search all adjacent tiles

for new_loc in location.Adjacent():

if board.IsValidLocation(new_loc) and new_loc not in previous_locations:

# make a copy of the previous locations list so our current list

# is not affected by this recursive call.

defensive_copy = list(previous_locations)

solutions.extend(self.DoSolve(board, defensive_copy, new_loc, new_word))

else:

if DEBUG:

print 'Ignoring %s as it is invalid or already used.' %(str(new_loc))

return solutions

Data structures

The data structure and algorithms used to implement the IsWord and HasPrefix methods are incredibly important.

I will examine three implementations and discuss the performance characteristics of each:

- Unsorted list

- Sorted list with binary search

- Trie

Unsorted list

An unsorted list is a terrible data structure to use for this task. Why? Because it leads to running time proportional to the number of elements in the word list.

class UnsortedListBoardSolver(BoardSolver):

def __init__(self, valid_words):

self.valid_words = valid_words

def HasPrefix(self, prefix):

for word in self.valid_words:

if word.startswith(prefix):

return True

return False

def IsWord(self, word):

return word in self.valid_words

While this is easy to understand and reason about, it is extremely slow, especially for a large dictionary (I used approximately 200k words for testing).

Took 207.697 seconds to solve 1 boards; avg 207.697 with <__main__.UnsortedListBoardSolver object at 0x135f170>

(This time is with the pruning turned on).

Sorted list

Since we know the valid words ahead of time, we can take advantage of this fact and sort the list. With a sorted list, we can perform a binary search and cut our running time from O(n) to O(log n).

Writing a binary search from scratch is very error prone; in his classic work Programming Pearls, Jon Bently claims that fewer than 10% of programmers can implement it correctly. (See blog post for more).

Fortunately, there’s no reason whatsoever to write our own binary search algorithm. Python’s standard library already has an implementation in its bisect module. Following the example given in the module documentation, we get the following implementation:

class SortedListBoardSolver(BoardSolver):

def __init__(self, valid_words):

self.valid_words = sorted(valid_words)

# http://docs.python.org/library/bisect.html#searching-sorted-lists

def index(self, a, x):

'Locate the leftmost value exactly equal to x'

i = bisect.bisect_left(a, x)

if i != len(a) and a[i] == x:

return i

raise ValueError

def find_ge(self, a, x):

'Find leftmost item greater than or equal to x'

i = bisect.bisect_left(a, x)

if i != len(a):

return a[i]

raise ValueError

def HasPrefix(self, prefix):

try:

word = self.find_ge(self.valid_words, prefix)

return word.startswith(prefix)

except ValueError:

return False

def IsWord(self, word):

try:

self.index(self.valid_words, word)

except ValueError:

return False

return True

Running the same gauntlet of tests, we see that this data structure performs far better than the naive, unsorted list approach.

Took 0.094 seconds to solve 1 boards; avg 0.094 with <__main__.SortedListBoardSolver object at 0x135f1d0>

Took 0.361 seconds to solve 10 boards; avg 0.036 with <__main__.SortedListBoardSolver object at 0x135f1d0>

Took 2.622 seconds to solve 100 boards; avg 0.026 with <__main__.SortedListBoardSolver object at 0x135f1d0>

Took 25.065 seconds to solve 1000 boards; avg 0.025 with <__main__.SortedListBoardSolver object at 0x135f1d0>

Trie

The final data structure I want to illustrate is that of the trie. The Wikipedia article has a lot of great information about it.

From Wikipedia:

In computer science, a trie, or prefix tree, is an ordered tree data structure that is used to store an associative array where the keys are usually strings. Unlike a binary search tree, no node in the tree stores the key associated with that node; instead, its position in the tree defines the key with which it is associated. All the descendants of a node have a common prefix of the string associated with that node, and the root is associated with the empty string. Values are normally not associated with every node, only with leaves and some inner nodes that correspond to keys of interest.

Snip:

Looking up a key of length m takes worst case O(m) time. A BST performs O(log(n)) comparisons of keys, where n is the number of elements in the tree, because lookups depend on the depth of the tree, which is logarithmic in the number of keys if the tree is balanced. Hence in the worst case, a BST takes O(m log n) time. Moreover, in the worst case log(n) will approach m. Also, the simple operations tries use during lookup, such as array indexing using a character, are fast on real machines

Again, I don’t want to reinvent what’s already been done before, so I will be using Jeethu Rao’s implementation of a trie in Python rather than rolling my own.

Here is a demonstration of its API via the interactive prompt:

>>> import trie

>>> t = trie.Trie()

>>> t.add('hell', 1)

>>> t.add('hello', 2)

>>> t.find_full_match('h')

>>> t.find_full_match('hell')

1

>>> t.find_full_match('hello')

2

>>> t.find_prefix_matches('hello')

[2]

>>> t.find_prefix_matches('hell')

[2, 1]

Unfortunately, there’s a bug in his code:

>>> t = trie.Trie()

>>> t.add('hello', 0)

>>> 'fail' in t

False

>>> 'hello' in t

True

# Should be false; 'h' starts a string but

# it is not contained in data structure

>>> 'h' in t

True

His __contains__ method is as follows:

def __contains__( self, s ) :

if self.find_full_match(s,_SENTINEL) is _SENTINEL :

return False

return True

The find_full_match is where the problem lies.

def find_full_match( self, key, fallback=None ) :

"'

Returns the value associated with the key if found else, returns fallback

"'

r = self._find_prefix_match( key )

if not r[1] and r[0]:

return r[0][0]

return fallback

_find_prefix_match returns a tuple of node that the search terminated on, remainder of the string left to be matched. For instance,

>>> t._find_prefix_match('f')

[[None, {'h': [None, {'e': [None, {'l': [None, {'l': [None, {'o': [0, {}]}]}]}]}]}], 'f']

>>> t.root

[None, {'h': [None, {'e': [None, {'l': [None, {'l': [None, {'o': [0, {}]}]}]}]}]}]

This makes sense, ‘f’ doesn’t start any words in the trie containing just the word ‘hello’, so the root is returned with the ‘f’ string that doesn’t match. find_full_match correctly handles this case, since r[1] = ‘f’, not r[1] = False, and the fallback is returned. That fallback is used by contains to signify that the given string is not in the trie.

The problem is when the string in question starts a valid string but is itself not contained in the trie. As we saw previously, ‘h’ is considered to be in the trie.

>>> r = t._find_prefix_match('h')

>>> r

[[None, {'e': [None, {'l': [None, {'l': [None, {'o': [0, {}]}]}]}]}], "]

>>> r[0]

[None, {'e': [None, {'l': [None, {'l': [None, {'o': [0, {}]}]}]}]}]

>>> r[1]

"

>>> bool(not r[1] and r[0])

True

>>> r[0][0]

# None

The issue is that his code does not check that there is a value stored in the given node. Since no such value has been stored, the code returns None, which is not equal to the SENTINEL_ value that his __contains__ method expects. We can either change findfullmatch to handle this case correctly, or change the __contains__ method to handle the None result as a failure. Let’s modify the find_full_match method to obey it’s implied contract (and be easier to understand):

def find_full_match( self, key, fallback=None ) :

"'

Returns the value associated with the key if found else, returns fallback

"'

curr_node, remainder = self._find_prefix_match(key)

stored_value = curr_node[0]

has_stored_value = stored_value is not None

if not remainder and has_stored_value:

return stored_value

return fallback

Let’s make sure this works:

>>> reload(trie)

<module 'trie' from 'trie.py'>

>>> t = trie.Trie()

>>> t.add('hello', 2)

>>> 'f' in t

False

>>> 'hell' in t

False

>>> 'hello' in t

True

OK, with that minor patch, here’s a first pass implementation of the solution using the trie:

class TrieBoardSolver(BoardSolver):

def __init__(self, valid_words):

self.trie = trie.Trie()

for index, word in enumerate(valid_words):

# 0 evaluates to False which screws up trie lookups; ensure value is 'truthy'.

self.trie.add(word, index+1)

def HasPrefix(self, prefix):

return len(self.trie.find_prefix_matches(prefix)) > 0

def IsWord(self, word):

return word in self.trie

Unfortunately, this is slow. How slow?

Took 2.626 seconds to solve 1 boards; avg 2.626 with <__main__.TrieBoardSolver object at 0x135f070>

Took 22.681 seconds to solve 10 boards; avg 2.268 with <__main__.TrieBoardSolver object at 0x135f070>

While this isn’t as bad as the unsorted list, it’s still orders of magnitudes slower than the binary search implementation.

Why is this slow? Well, it’s doing a whole lot of unnecessary work. For instance, if we want to determine if ‘h’ is a valid prefix, this implementation will first construct the list of all words that start with h, only to have all that work thrown away when we see that the list is not empty.

A much more efficient approach is to cheat a little and use the previously discussed method _find_prefix_match which returns the node in the tree that the search stopped at and how much of the search string was unmatched.

By using this method directly, we can avoid creating the lists of words which we then throw away. We modify the HasPrefix method to the following:

def HasPrefix(self, prefix): curr_node, remainder = self.trie._find_prefix_match(prefix) return not remainder

With this optmization, the trie performance becomes competitive with the binary search:

Took 0.027 seconds to solve 1 boards; avg 0.027 with <__main__.TrieBoardSolver object at 0x135f230>

Took 0.019 seconds to solve 1 boards; avg 0.019 with <__main__.SortedListBoardSolver object at 0x135f330>

Took 0.199 seconds to solve 10 boards; avg 0.020 with <__main__.TrieBoardSolver object at 0x135f230>

Took 0.198 seconds to solve 10 boards; avg 0.020 with <__main__.SortedListBoardSolver object at 0x135f330>

Took 2.531 seconds to solve 100 boards; avg 0.025 with <__main__.TrieBoardSolver object at 0x135f230>

Took 2.453 seconds to solve 100 boards; avg 0.025 with <__main__.SortedListBoardSolver object at 0x135f330>

It is still slower, but not nearly as bad as before.

Solving the board in the screenshot

With all this machinery in place, we can run the original board in the screenshot through the algorithms:

words = ReadDictionary(sys.argv[1])

print 'Read %d words' %(len(words))

trie_solver = TrieBoardSolver(words)

sorted_list_solver = SortedListBoardSolver(words)

b = Board(4, 4)

b.board = [

['l', 'qu', 'r', 'e'],

['s', 'l', 'u', 's'],

['a', 't', 'i', 'c'],

['n', 'r', 'e', 'n']

]

print 'Solving with binary search'

sorted_solutions = sorted_list_solver.Solve(b)

print 'Solving with trie'

trie_solutions = trie_solver.Solve(b)

# Results should be exactly the same

assert sorted_solutions == trie_solutions

for solution in sorted(sorted_solutions):

print solution

words = sorted(set([s.word for s in sorted_solutions]))

print words

The results appear after the conclusion.

Conclusion

I have presented both pseudocode and Python implementations of an algorithm for solving the classic Boggle/Scramble With Friends game. In the process, we saw such concepts as recursion, depth first search, optimizing code through pruning unfruitful search branches, and the importance of using the right data structure. This post does not aim to be exhaustive; I hope I have piqued your interest for learning more about tries and other lesser known data structures.

For results, the patched trie implementation, and the driver program, see below. To run the driver program, pass it a path to a list of valid words, one per line. e.g.

python2.6 solver.py /usr/share/dict/words

https://gist.github.com/2833942#file_trie.py

For mobile users, the link can be found at https://gist.github.com/2833942